The year 1876 marked the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, a momentous event in the history of the United States. To commemorate this occasion, the nation decided to host its first official World’s Fair, also known as the Centennial Exposition, in Philadelphia, the city where the Declaration was adopted. The Centennial Exposition was not only a celebration of American independence, but also a showcase of American art and industry, as well as a display of international culture and commerce. In this blog post, I will explore some of the highlights and significance of this remarkable event.

Planning and Preparation

The idea of holding a World’s Fair in Philadelphia was first proposed by John L. Campbell, a professor of mathematics and astronomy at Wabash College, Indiana, in 1866. He suggested to the mayor of Philadelphia, Morton McMichael, that such an exposition would be a fitting way to honour the centennial of the nation’s birth. The idea was met with enthusiasm by the city council, the state legislature, and the federal government, and soon a Centennial Commission was formed to oversee the planning and execution of the project.

The commission faced many challenges and obstacles along the way, such as finding funding, securing participation from other nations, and selecting a suitable site for the exposition. After considering several locations, including New York City, Washington D.C., and Chicago, the commission settled on Fairmount Park, a large green space along the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. The park offered ample space for the construction of more than 200 buildings and structures, as well as scenic views and easy access to transportation.

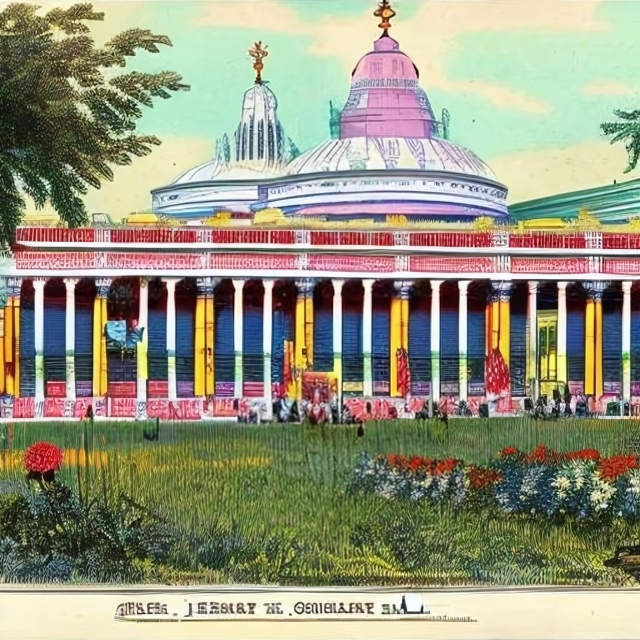

The commission hired Herman J. Schwarzmann, a German-born architect who had worked on several public buildings in Philadelphia, to design the layout and appearance of the exposition grounds. Schwarzmann envisioned a grand and harmonious ensemble of buildings that would reflect various architectural styles and historical periods. He also incorporated elements of landscape design and engineering to create fountains, gardens, bridges, and roads that would enhance the beauty and functionality of the site.

The construction of the exposition began in 1873 and lasted until 1876. It involved thousands of workers and contractors who used various materials and techniques to erect the buildings and install the exhibits. Some of the buildings were permanent structures that still stand today, such as Memorial Hall (now the Philadelphia Museum of Art), Horticultural Hall (now part of Fairmount Park), and Machinery Hall (now demolished). Others were temporary structures that were dismantled after the exposition closed, such as Agricultural Hall (a large wooden barn), Main Exhibition Building (a colossal iron-and-glass pavilion), and Government Building (a neoclassical edifice).

Opening and Operation

The Centennial Exposition officially opened on May 10th, 1876, with a grand ceremony attended by President Ulysses S. Grant, Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, and other dignitaries and celebrities. A large crowd gathered to witness the hoisting of flags, the firing of cannons, the playing of bands, and the speeches of officials. President Grant declared the exposition open by pressing a telegraph key that activated a bell in Independence Hall and signalled to all parts of the country that the celebration had begun.

The exposition remained open for six months, from May 10th to November 10th, 1876. During this time, it attracted nearly 10 million visitors from all over the world. The visitors came by various means of transportation, such as railroad, steamboat,

carriage, and on foot. They paid 50 cents for admission (25 cents for children) and could explore the vast array of exhibits and attractions that spanned more than 285 acres of land.

The exhibits were divided into several categories: art; education; engineering; government; horticulture; machinery; manufactures; mining; agriculture; transportation; foreign; women’s work; Indian school; Negro department; sanitary commission; historical relics; fine arts; photography; musical instruments; fireworks; balloons; etc. Each category had its own building or section where visitors could see displays of products, processes, inventions, artworks, specimens, models, and more.

Some of the most popular exhibits included:

– Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone

– Thomas Edison’s phonograph

– Elisha Otis’s elevator

– Christopher Sholes’s typewriter

– Elias Howe’s sewing machine

– Joseph Glidden’s barbed wire

– John Ericsson’s solar engine

– George Westinghouse’s air brake

– Samuel Colt’s revolver

– Remington’s rifles

– Singer’s sewing machines

– Tiffany’s jewelry

– Gorham’s silverware

– Heinz’s ketchup

– Hires’s root beer

– Anheuser-Busch’s beer

– Borden’s condensed milk

– Kellogg’s corn flakes

– Hershey’s chocolate

– Campbell’s soup

The exposition also featured exhibits from 35 foreign countries, such as France, Germany, Britain, Japan, China, Turkey, Egypt, Brazil, Mexico, Canada, etc. These exhibits showcased the culture, history, and industry of each nation, as well as their diplomatic and commercial relations with the United States. Some of the most notable foreign exhibits included:

– The Statue of Liberty’s arm and torch (France)

– The Eiffel Tower’s model (France)

– The Corliss steam engine (Britain)

– The Koh-i-Noor diamond (Britain)

– The Japanese bazaar and garden (Japan)

– The Chinese pagoda and temple (China)

– The Turkish mosque and bazaar (Turkey)

– The Egyptian obelisk and sphinx (Egypt)

– The Brazilian coffee pavilion (Brazil)

– The Mexican pyramid and fountain (Mexico)

The exposition also offered various forms of entertainment and amusement for the visitors, such as concerts, lectures, demonstrations, parades, fireworks, balloons, etc. Some of the most famous performers and speakers who appeared at the exposition included:

– P.T. Barnum and his circus

– Buffalo Bill and his Wild West show

– Tom Thumb and his wife

– Mark Twain and his humour

– Susan B. Anthony and her suffrage

– Frederick Douglass and his abolitionism

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his poetry

– John Philip Sousa and his band

Impact and Legacy

The Centennial Exposition was a huge success in terms of attendance, revenue, publicity, and prestige. It generated more than $4 million in profits for the organizers and exhibitors, as well as millions more for the city of Philadelphia and the state of Pennsylvania. It received extensive coverage in the local, national, and international press, as well as in books, magazines, newspapers, photographs, paintings and souvenirs. It enhanced the reputation of Philadelphia as a cultural and commercial centre, as well as the image of the United States as a modern and progressive nation.

The Centennial Exposition also had a lasting impact on American art and industry, as well as on American society and culture. It stimulated the development of new technologies, products, market, and industries that would shape the future of the country. It inspired the creation of new forms of art, design and architecture that would influence the aesthetic tastes of the public. It fostered a sense of national pride, identity and unity among the diverse groups of people who participated in or visited the exposition. It also sparked a wave of interest in education, history and culture that would lead to the establishment of new museums, libraries and monuments across the country.

The Centennial Exposition was a landmark event in American history that marked the end of one era and the beginning of another. It was a celebration of American independence, but also a declaration of American interdependence with the rest of the world. It was a showcase of American art and industry, but also a reflection of American society and culture. It was a spectacle of wonder and delight, but also a source of knowledge and enlightenment.

References

– Rydell, Robert W., All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984).

– Atterbury, Paul, ed., A.W.N. Pugin: Master of Gothic Revival (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

– Bolotin, Norman and Christine Laing. The World’s Columbian Exposition: The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

– Burton Benedict. The Anthropology of World’s Fairs: San Francisco’s Panama Pacific International Exposition of 1915. London: Scolar Press; Berkeley: University of California Press; 1983.

– Findling, John E., and Kimberly D. Pelle, eds. Encyclopedia of World’s Fairs and Expositions. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008.

– Greenhalgh, Paul. Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851-1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988.

– Harris, Neil. Humbug: The Art of P.T. Barnum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.

– Mattie, Erik. World’s Fairs. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998.

– Rydell, Robert W. All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

– Rydell, Robert W., John E. Findling, and Kimberly D. Pelle. Fair America: World’s Fairs in the United States. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000.

– Badger, Reid R. The Great American Fair: The World’s Columbian Exposition and American Culture. Chicago: N. Hall Co., 1979.

– World’s Fairs | AM. https://www.amdigital.co.uk/collection/worlds-fairs

– Encyclopedia of World’s Fairs and Expositions Hardcover – Amazon.co.uk. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Encyclopedia-Worlds-Fairs-Expositions-Findling/dp/0786434163

– World’s Fairs: A Global History of Exhibitions. https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/2150

– World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Expositions – Amazon.co.uk. https://www.amazon.co.uk/World-Fairs-Century-Progress-Expositions/dp/0226732363

– Fiction (and Film) Set at World’s Fairs and Expositions – Library Booklists. https://librarybooklists.org/mybooklists/worldsfairs.htm.

– Centennial Exposition – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centennial_Exposition

– Philadelphia Centennial Exposition | trade fair, Philadelphia …. https://www.britannica.com/event/Philadelphia-Centennial-Exposition

– The Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876. https://lcpimages.org/centennial/

Tags

Divi Meetup 2019, San Francisco

Related Articles

Unappreciated Greatness

Life and Legacy of Jahangir of the Mughal Empire. Jahangir ruled over one of the largest empires in human history during his lifetime, yet few people outside of South Asia have heard of him. I aim to shed light on the life and legacy of this remarkable figure,...

The Plague Doctor’s Diary

A Personal Account of the Turin Epidemic of 1656. I am writing this diary to record my experiences and observations as a plague doctor in Turin, the capital of the Duchy of Savoy, during the terrible epidemic that has afflicted this city and its surroundings since the...

The Timeless Beauty of Bustan

Unveiling the Secrets of Saadi Shirazi's Masterpiece.In the realm of Persian literature, few works have captured the essence of love, spirituality, and morality quite like Bustan (The Orchard) by Saadi Shirazi. This 13th-century masterpiece has left a lasting impact...

Stay Up to Date With The Latest News & Updates

Explore

Browse your topics of interest using our keyword list.

Join Our Newsletter

Sign-up to get an overview of our recent articles handpicked by our editors.

Follow Us

Follow our social media accounts to get instant notifications about our newly published articles.